The Last Time I Ate Treif

A Contrary Pizza

Speaking of Maimonides. His “Guide for the Perplexed” was not universally applauded in Jewish circles. There are many reasons for this, and none seem too important today. His other great work was an encyclopedic compilation of Jewish law. There is renewed interest in this work with thousands taking part in learning daily portions of it. One of the reasons it is so popular is that Maimonides wrote it a thousand years ago in a beautiful Hebrew, the same Hebrew spoken in Israel today. This is in contrast to the “Guide for the Perplexed” which was written in Judeo-Arabic (Arabic written with Hebrew letters). More importantly, it is in contrast to the source for his compilation of Jewish Law, the Babylonian Talmud. There is some Hebrew in the Talmud, but the vast majority of it is written in Babylonian Aramaic. The Talmud is not a book that can be read in the normal sense of the word. To overly simplify, it is a collection of statements of Jewish law originally transmitted orally, the Mishna (this is the part that is in Hebrew), with each Mishna followed by a discussion of those statements in Aramaic, the Gemara, by later generations of Jewish scholars. These discussions and opinions span hundreds of years and scores of different Rabbis and centers of learning and the subject matter is vast—as vast as the story of life. As all-encompassing as it strives to be, this format makes the Talmud a closed document. How closed? Traditionally the initiate is expected to study for at least ten years, 4-6 hours a day minimum mostly with a study partner side by side, and then alone according to his ability, with periodic review and oral examination by a Rabbi. With this in hand, in Jewish learned circles, the student will be considered conversant with the Talmud.

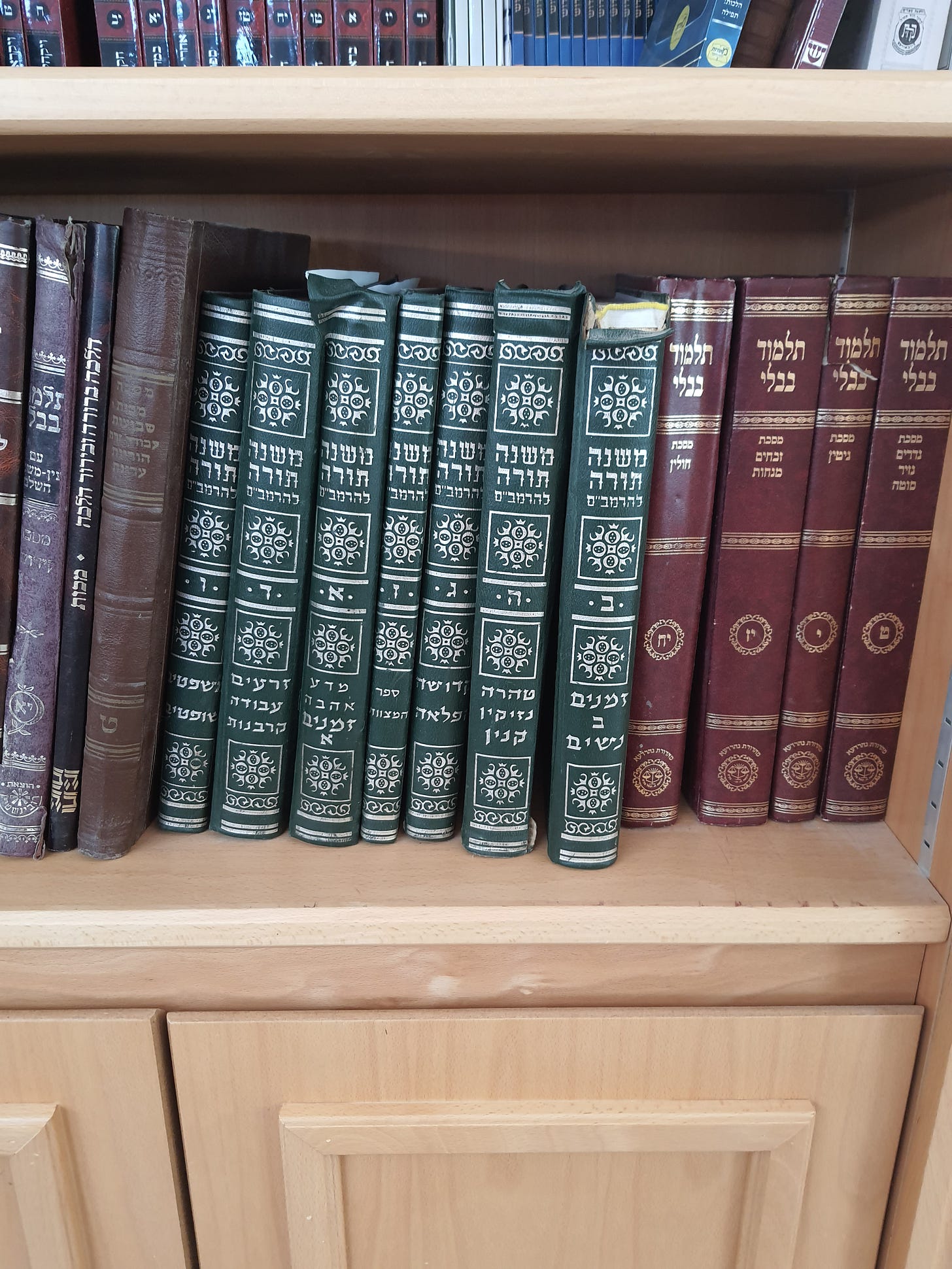

Here is a picture of Maimonides’s compilation of Jewish law, the Mishne Tora, the first addition to my Jewish library that looked and felt and smelled like the real thing.

Here it is in the library of our synagogue next to the Talmud, our having donated it.

Looking back at my younger self, from the distance of a grandfather, I relive the excitement I felt at the time. A new language, a new belief, a new life. I was feeling invigorated, and powerful in my castle, which at that time, about one year into the conversion process, was in an enclosed porch in a rented apartment on Palmach street half-way up Mount Carmel in Haifa, on a rise behind the municipal sports arena but more importantly, within direct site of Pizzeria Rimini. The eyes that were poring over the writings of the great medieval Jewish philosopher were the same eyes looking out the window now and then at one of the venues where they would serve you a pizza with some salami on it. Meaning strictly non-kosher. Treif. I don’t want to give the impression that I was torn between Jewish law and salami pizza, but late at night when the going got tough with Maimonides I would look over towards the lit oasis of Pizzeria Remini and could almost smell it. Again, I don’t want to go too far with this, but pizza really can be seen as the quintessential unholy food. Pizza after all is a food that is chomped on. It is a food you could grab on your way to or returning from idol-worship; empty calories fueling the empty lies of false prophets. There is nothing funnier in this world than seeing someone try to eat pizza elegantly, and we have all witnessed at some time in our lives the poor lost soul eating pizza with a knife and fork. But then again, I am showing my age. We have healthy pizzas now. You cannot pick them up with your hand because all the healthy stuff falls off. Back then there was only one way to eat pizza: stuff, chomp, beer, burp, repeat. The perfect street slogan for the coming pizza riots. The crowd chanting: stuff, chomp, beer, burp, repeat!

Well, it turns out that that damn pizza joint was the pistol hanging on the wall in the first act of a Chekov play. One of the things made clear to a potential convert to Judaism is that one cannot keep all of the commandments; for example, one cannot observe the Shabbat completely. Reserved for Jews only. There is a warm-up, though. One does observe commandments, just not all of them. What this means is that at some point during the Shabbat one needs to do something that violates the Shabbat. The idea of course is not to do this in public. In practice, I would just turn the bathroom light on and off as needed. No biggie. Here and there, in the coming and going of life, I would consciously choose to violate other commandments in private, as quietly as possible. I was still not Jewish. Now aside from my Shabbat “arrangement,” I also cut myself some slack when it came to the whole milk/meat separation thing. You cannot eat them together. By this time, I was beyond allowing myself salami and cheese sandwiches, but the proscription of waiting six hours after eating meat before eating milk products was shortened by up to three hours. A common statement to myself at the time: “Still not Jewish.”

And this held strong until the night two Canadian classmates from the University of Haifa invited me out for pizza. Perry and Larry were drinkers, serious drinkers. They had one rule: not a drop before noon. At noon the first bottle of vodka was opened, and it continued from there. They reminded me of an approach to alcohol that I knew from my late father. It was that a real man knows how to “hold his liquor.” In that sense they were real men. In a curious way they functioned quite well while under the influence, which included functioning during classes that met in the afternoon. One of them functioned so well as to find his future wife while in this state. Having little knowledge of Canadians, I assumed that it was a national trait. Heavy drinkers who did not get drunk. I was peripheral to their shenanigans, but we were quite friendly. Friendly enough that on the day before they returned to Canada to continue their lives as Canadian Jews, they invited me to join them at Pizzeria Remini. A going-away party.

For me to accept was wrong in so many ways. Obviously, it was a flagrant public violation of the dietary laws, so I would have to pocket my yarmulka, something I hadn’t done since starting to wear one about six months before. It wasn’t a big yarmulka, just a rounded pad of woven thread, but it symbolizes so much in the religious Jewish world. The type of weave, the size, the color, whether it is weaved at all—all this makes one identifiable in seconds to other wearers and to many non-wearers, down to knowing how one will vote in the next elections, or which type of yeshiva one learned at or which type of army service one has done or will do (or will not do). In general, wearing one symbolizes that the wearer (up until recently strictly male) is aware of the Creator in the Heavens above and is a declaration that one leads one’s life in accordance with that awareness. At the same time, it should be noted that one of the most iconic images on Israeli news television is that of notorious crime bosses appearing in court wearing enormous virgin-white yarmulkas. That extends the symbolism of that round patch of cloth far in quite the different direction. And all of this was in play when I placed mine in my pocket. Why didn’t I just leave it at home? I don’t know. Maybe I had a need that it be within arm’s reach for emergencies. In other words, I was orchestrating a temporary breakdown of my adopted framework of life, but something deep within myself told me that I might be in need of a life preserver at some point in the evening. Throwing a life-preserver from a sinking ship to oneself doesn’t make sense from the git-go, because you’re either on the ship or in the water but pulling a yarmulke out of my pocket in a crisis somehow did make sense at the time. In short, the thinking: hour and a half, tops. I still wasn’t Jewish.

The yarmulke was the least of my problems. There was another major issue. Of course there was. In truth it was a moral issue, but once I had overcome my reservations the issue became tactical: how to engineer this event so that no damage would occur. Damage meaning word getting to the Rabbinical Court overseeing my conversion that I was comporting myself publicly in a manner that was unbecoming of a prospective convert to Judaism. The problem was as follows: Pizzeria Remini was across the street from the municipal sport center, next to a gas station. That was it, just the two businesses and one basketball arena that was in use once a week, in total isolation. In those days in Israel the gas stations themselves didn’t have their own convenience stores. So, if anyone were to approach those two buildings on foot it was clear that a salami pizza was the goal. True, I was not going to run into any religious acquaintances from the nearby synagogue I attended, but it was a long, exposed walk across the street—a main throughway connecting three neighborhoods—and anyone driving by would know where I was heading. Also, I had non-religious neighbors and friends who might be eating at the restaurant themselves. Running into them would be just as bad since it would confirm to them that religious Jews were just a bunch of hypocrites. Like a crime boss wearing a yarmulke at his arraignment. Everything was topsy-turvy in my mind. But three things were already certain. I was going. I would drink more than was good for me. And the excursion was going to be eventful. Yes, a premonition. I knew something bad was going to happen. And only something bad could happen. The question then becomes: why do some of us keep placing one foot in front of the other in a slow, seemingly calculated stroll towards what we know in the deepest regions of our soul will be bad tidings? A whole film genre—horror films—rose out of this conundrum (“Don’t open that door you idiot!”). Eventually I came to believe that it was less of a stumbling, bumbling movement but more of a lizard-brained existential quest.

Those of you conversant with the Bible might have recognized the surroundings of these events. Haifa is mostly situated on Mount Carmel. The same Mount Carmel where Elijah the prophet had his big showdown with the prophets of Baal. Elijah cries out to the children of Israel (loose translation): “How much longer will you all be sitting on the fence. Make your choice! The Baal or the true God!”

Here are a few samples of different translations of the verse.

Hopping or limping between two opinions or jumping between two concepts. I wasn’t aware of it at the time (but I was, wasn’t I). I was on the fence. I was hopping limping and jumping. For the sake of a beer and some pizza and some fun with friends, I was willing to suspend the world view that had brought me to my decision to convert. The world view that accepted as irrefutable fact that the three-thousand-year-old prophecy of the true God was coming to life in front of the entire world: the return of the Jewish people to their ancestral homeland.

I believed that was what was happening then, and I wanted with all my soul to be a part of it. I still do to this day.

What can I say? It was all fresh back then, even after a year in the process, and it took just a slight nudge to convince me to hop on over to Baal’s venue. Junk food. Salami Pizza. Empty calories for an empty head. Treif.

What was about to unfold would cure me of my hopping from then until now, but I would walk away from the event with a limp. Jacob wrestled all night with an angel, to limp away in the morning, albeit with holy esoteric knowledge. There are always two roads: one leading to Blessings, Good, and Life, the other leading to Curses, Evil, and Death. I chose the road which seems unfortunately the most travelled and joined my friends at Pizzeria Remini where the festivities were well under way. It didn’t take long before my eyes glazed over from the beer. In time, I felt that I was on a stage. Large windows surrounded the dining area on three sides. Outside was the dark of night, inside the lights on a stage, much stronger than was necessary for eating pizza and drinking beer. I knew an audience was outside looking in on the stage. I knew it. Anyone standing outside could see everything in the restaurant. I grew despondent, knowing that my fate was sealed. Larry and Perry, seeing me down, offered their solution: another round of beers. For a short while I did feel that maybe the evil decree would be rescinded this one time, until I peered into the darkness and saw a milky white face sticking out at an angle from behind the restaurant’s dumpster like some sort of jokester moon. Only a face that spent most of its time indoors under fluorescent light studying the Talmud could have been so white, allowing itself to be seen from inside the restaurant. Jacob had his angel; this was mine. There could be only one reason that such a person would be within miles of that place, and that was to spy on me. He was a messenger from the Haifa Rabbinate following me. A million things ran through my mind at once, not least the wonder surrounding the fact that after about a year of being a reasonable candidate for conversion, the one time I slipped-up badly they were on the scene.

Busted!

Seeing that I saw him, the white moon jerked back into hiding behind the dumpster. The moment he was out of sight I began doubting what I had seen. Was my mind playing tricks on me—again? No, I was seeing sharp and clear. My companions noticed me staring out the window.

-What’s wrong Bill?

-You won’t believe me if I told you.

-You’re not looking so good, Bill.

-I just saw a black-hat type. I think he’s from the Rabbinate. He’s spying on me.

-Bill’s seeing Rabbis again!

They laughed as I grew despondent.

Like many under the influence of alcohol, I would normally have tended towards self-pity. Here, though, I was at a point where I had invested my entire future in becoming an observant orthodox Jew and it just couldn’t stand that a moment like this would destroy my chances—a moment that was still allowed to me according to Jewish law, well, in a way was still allowed to me. I knew what had to be done. It was time to wrestle. I had to grab him and shake him up and to explain myself. If he would just give me a minute…

I was on my way to the door. The Canadians were full of glee.

-Be careful Bill (my name at the time). Keep a look out for Rabbis.

-Watch your back, Bill. You can never be too careful.

They of course did not believe that I was being spied upon. In pursuit, I lunged through the door and managed two steps towards the dumpster on my left before I fell to my knees. I leaned forward, and without heaves or hacking I returned the pizza to the Earth. It slid out like dog food from a can. Quietly, peacefully, with maybe a bit of a slurp. I was not drunk and not sick; this was a different kind of upheaval. And when I stood up, I was in a different place. I didn’t even look towards the dumpster. There would be a price to pay, and I would pay it (there was, and I did; it took me another two and a half years to convert). I looked towards my friends in the restaurant and could see the worry on their faces. I gave them a thumbs up and was dumbfounded when the entire crowd in the restaurant began cheering me. There is a term for it. Those Canadians knew how to party. I was happy for them and their new friends. I gathered myself and took a last look at Larry and Perry. They sat side by side facing me through the window, smiling. I raised my hand high in a salute of friendship knowing I was unlikely to see them again. They, to their credit returned the salute, beers raised high, understanding that I was not just taking leave of them. I was leaving an entire world behind. They respected what I was doing. After all, they were Jews.

As I slouched across the street towards my apartment and my future, I couldn’t shake the vision of my friends in the restaurant sitting side-by-side, acting as some sort of secular Rabbinical court, authorizing me to take final leave of the world I had known till then. I had thought that this had been accomplished when I had made my official request to start conversion proceedings at the Haifa Rabbinate about a year earlier. It seems that for a change of this magnitude a powerful physical upheaval is needed, to urge the soul to move in a new direction. This needed to be learned. It needed to be lived.

Somewhat sober, I entered my apartment. My roommate Yossi was sitting in the living room with his best friend Moti. I had to walk through them to get to my porch. To get to my Maimonides. I was not looking good at the time, and I was not smelling good. But given all that I was in a heightened state of awareness and as soon as I heard them, I stopped in my tracks.

-What did you just say? I asked Yossi.

Yossi looked at me, friendly, sizing me up and said facetiously

-Going to study some Maimonides Bill?

-Yes, I am. But what were you two just talking about?

It needs to be said here that these two friends were at least outwardly secular Jews at that time. They had studied together at the Reali military prep school a bit higher up on Mt. Carmel. Reali is a prestigious high school, secular and liberal. The cadets at the military prep school learned alongside the regular students at Reali, and in addition began military training so that after a short basic training, they would be commissioned as officers in the Israeli Defense Forces right after high school. Think Andover with ROTC.

Yossi was doing his masters in English literature at Haifa University. From there I knew him. Moti was somewhat of a wunderkind of the philosophy department, already at a young age a popular lecturer. Yossi, still assuming that I was in my cups, continued.

-We are debating ourselves about the existence of God.

He was being playful with me, but from what I had heard of their conversation when I walked in, I knew that that was precisely what they were discussing. I looked from one to the other and spoke calmly to Yossi.

-You are Jews. You have a God. You have commandments passed down through the ages. You have a destiny to fulfil on which all of Humanity depends. What the hell’s wrong with you two? Get on with it already.

I paused for effect and then continued to the porch, trailing a stench of vomit and treif.

I like to think that what I said had an effect on them. Though Yossi and I had had long talks about Shakespeare, and classical music verses jazz, we had never spoken about our personal beliefs in a serious manner. If we had, I might have learned that his discussion with Moti was one of many continuous and serious discussions. They, along with another friend from Reali eventually did become officers, in time for the Yom Kippur war. Their coming to terms with their experience from the war led them to a process of repentance, of return to traditional Judaism. The three of them to this day are observant Jews. By the time of their discussion that I overheard, they were near the end of the process. As I said, this I did not know at the time. If I had, I like to think that I would not have so self-righteously and enviously berated them in such a manner. Then again, maybe it was precisely that “in-your-face” declaration, whilst “in-my-cups”, that helped them to take the final step and return to the beliefs and practices of their forefathers. As I said, I like to think that.

The three comrades came to be known by their friends from Reali and Haifa University as “the three who did not return (from the war).” Meaning, they did not return to the secular and liberal lives that they had lived before. Instead, they “returned in repentance,” a Jewish term meaning the regret at having been astray and a renewal of a commitment to the God of Israel.

Having finally reached my desk, I opened the window wide and opened Maimonides to the chapter on the laws of repentance, and cried out:

-Wake up you sleepy ones from your sleep and you who slumber, arise. Inspect your deeds, repent, remember your Creator!

In Hebrew this phrase has an unforgettable rhythm, learned by heart by generations of Jews, and my voice carried it on high, reverberating throughout the neighborhood like a latter-day Elijah, or at least throughout our apartment. I heard Yossi and Moti laughing.

-Hey Bill, keep it down. The neighbors will complain.

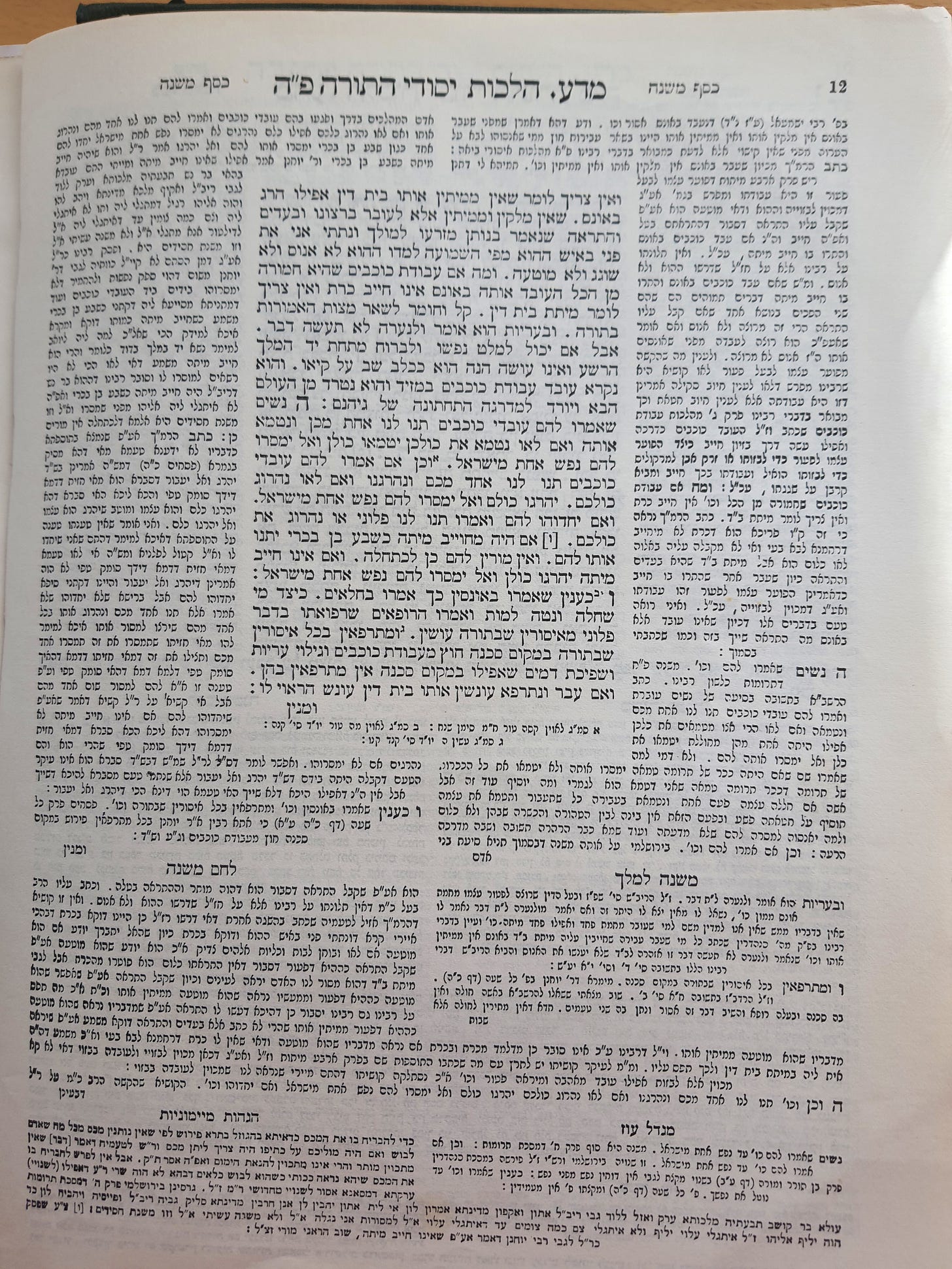

Here is the full text of that chapter of the Laws of Repentance.

Neither they, the three who did not return but did return, nor I, the one who joined, haltingly, with hiccups, could keep it down. Each of us in our own way moved closer to the Creator, the God of Israel, and to this day strive to awaken from our slumber, to inspect our deeds, and to repent.

This is the Ehud I've been waiting for, the Ehud I've always believed in, the Ehud who has something to share with the world and has found his voice in order to do so.

I think the thing that leads us down to the dark basement in the horror movie is a very deep visceral need of some sort. Not a flippant drive, but a lack so profound it defies rational thought. I guess you could call anything lizard brain but I think that the deepest emotions that are incredibly difficult to access consciously are important; they are our warning system. They are very difficult to handle because it’s hard to even know what they are, and very powerful but they come to say something important. I posit that the behavior stops when the need is understood and met.