Enthusiasts

Settle down there now. Easy does it. Let's talk it over.

Sometimes things come together in unexpected ways. I finished a round of writing about Ulysses and was finding it difficult to get back on track with A Pisgah Site. Bloom’s summing up of his encounter with the Zionist pork butcher Dlugacz kept echoing in my head. “Enthusiast,” Bloom labeled him. Joyce had at least one “enthusiastic” Zionist acquaintance in Trieste, who reportedly tried to win him over to the cause. It's hard to tell what he expected of Joyce…to write a prospectus? Which of course Joyce did, in Ulysses. By all accounts Joyce was skeptical of the whole Zionist project; it seemed strange and improbable. And yet, it was precisely during the years that he was writing Ulysses (1914-1922) that the Zionist project became more than a dream.

That is what Theodor Herzl said. “If you will it, it is not a dream.” Is this the truism that fuels the engine of humankind? A kind of secret to success wielded by those with that self-same will and the determination to use it? It sounds as if it could be, and it certainly turned out that way for the Zionists. Is an excited will sufficient to achieve goals? Is change only possible through the agency of enthusiasts? Or is there more importance to the object of the will, the object of enthusiasm, a worthy object being necessary to sustain the will-to-achieve and necessary for recruiting the collective will to achieve that desired goal? What or who determines what is worthy? The victors, the strong, who prevail through might and write history? Survivors of all types, whose very presence is testimony to a different kind of history, one of human endurance? These questions, as simplistic as they are, point the way towards an understanding of the machinations of human activity on this Earth.

Orthodox Jews read the Torah, the first five books of the Bible, over the course of the Jewish year during prayers on the Sabbath. While I was pondering Joyce’s enthusiast, what passed beneath my eyes during the Bible reading on a recent Shabbat was the story of that most enthusiastic of enthusiasts, Pinchas. His story closes up the portion read on one Shabbat, that of Balak, and opens the portion named after him read on the following Shabbat. Yes, the same Phineas who took the law into his own hands and speared the mixed couple that was making the beast with two backs in public. This specific incident in the Torah triggered volumes of commentary because not only was Phineas not punished for taking the law into his own hands, he received an everlasting covenant from the Creator for himself and his offspring. What kind of social stability is possible when the Arbiter of All blesses such an act? Note that the Creator gives his blessing after the fact. What are we to learn from Phineas’ mind-set when he took up the spear? We are not told that he received a command, or that he heard a voice. How do we perceive and measure such enthusiasm? More to the point: when do we decide when enough is enough, and then take matters into our own hands? Modern civil society answers directly: never. In addition to that determination that by the way leaves us with no way to pre-empt a Hitler or a Stalin, it also leaves us astounded and confused when the rules are broken. We wait, meekly, sometimes in mourning, for our leaders to reassure us that the social order still holds.

Whatever we can glean from the questions raised in the previous paragraph, and the myriad possible answers to them, the questions and the answers themselves are products of willful acts, albeit of the intellect. These willful acts of interpretation can themselves reach extremes, such as totalitarian indoctrination, resistance of which usually means death to the resister. At such extremes, dissent is not tolerated.

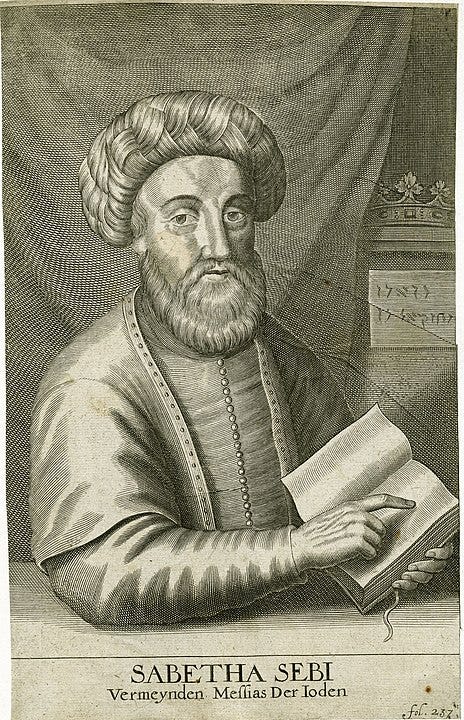

As happens in life, when it rains it pours. It wasn’t just the Bible portion of Pinchas I was reading at this time. I was also reading “Belonging, The Story Of The Jews 1492-1900,” by Simon Schama. In particular, the section on Shabtai Zevi, who managed to convince the entire Jewish diaspora of the mid seventeenth century that he was the Messiah. Another enthusiast. Less him, really, than his proto-public relations officer, Nathan of Gaza. I had always wondered how the wise Jews of the late middle ages were duped by this false messiah. Jews are always skeptical of those claiming to be the Messiah. My own worry is that when the Messiah does finally show up, he will be so badgered by questioning that he will not have any power left to usher in the Redemption. It turned out that the Jews of the world were convinced by the bona fides of Nathan of Gaza. Nathan was known as a wise man, but what really gave credence to his support of Shabtai was the fact that he was a wise man from the Holy Land. In addition it had been a bad past five hundred years for the Jews, starting with the Crusaders sharpening their swords against Jews on the way to the Holy Land (again!) right through to the expulsion of the Jews from Iberia. The Jews of the world had reached a point where they couldn’t fathom things getting worse, for them proof that the appearance of the Messiah must be imminent.

How did Shabtai convince Nathan? He didn’t. It turns out that it was Nathan who convinced Shabtai that he was the Messiah. It was an example of the “Jerusalem Syndrome” twice displaced: displaced geographically from Jerusalem to Gaza, and displaced objectively from the self to another. That may have helped Nathan’s cause, when he began writing letters to the great centers of Judaism throughout the world, proclaiming Shabtai as the Messiah. There is no doubt that Nathan was a true believer in Shabtai—he continued to believe that he was the Jewish Messiah even after Shabtai converted to Islam. So that, though Nathan was by all accounts a Jew steeped in Jewish law, and a mystic, it seems that it was his skill at public relations that pulled all the Jews of the world into believing in Shabtai. Letter writing. Remarkable. The power of the written word.

And what of the enthusiasts, literally the entire Jewish population of that time? Dancing in the streets, dancing in the hearts of these poor Jews who had been waiting and hoping for sixteen centuries for and end to their travails. It was finally happening! How did a Jew of the time know this for sure? That wasn’t even a question to be asked. Everyone knew it, including Jewish leadership and great Rabbis from near and afar. There was no room for doubt at all. Many of their Christian neighbors got caught up with it too. Once you get those kinds of numbers, the movement takes on a life of its own. Everyone knows the truth. The issue is settled. Keep dancing. For these Jewish enthusiasts, a worse denouement could not have been imagined, when their Messiah opted for a comfortable life in Ottoman Turkey rather than being beheaded.

In modern Israeli history, we have the infamous enthusiast Yigal Amir. Their are scores of conspiracy theories already, and many serious unanswered questions. For the purposes of this article, we can take him at his word that though he did not fire the shots that killed Prime Minister Rabin, he would have happily done so if given the opportunity. He claims from his prison cell that he knew that there were blanks in his gun put there by the security services—they admit as much—and that he went through the actions (on publicly available video footage) for some reason or another. Whatever really happened, the fact that he freely admits that he would have murdered the Prime Minister is what interests us here. Who gave him that right? Yes, there was talk of some right-wing Rabbi or another who labeled Rabin a “moser,” or a Jew who causes other Jews to be in mortal danger (Rabin doing this by allying with Yasser Arafat whose minions were busy murdering Israelis by the thousands at that time) and as such it is permitted to stop him, even by murder. In the end, though, it was Amir who fired the live bullets or the blanks. He took it upon himself to be “a man of action.”

One can easily see where this is going. The crucial difference between Phineas and Amir is that Phineas actually did hear a voice from heaven, for he was present at Mount Sinai when the Law was given to the Jews. And since the Rabbis tell us that if one thing is true about the Creator, it is that He hates lewdness and sexual depravity, Phineas was acting in accord with a Divine will that he had heard expressed miraculously with the rest of the Jewish people at Sinai.

And Yigal Amir? That’s just it. Jewish tradition holds that this Divine will is passed down faithfully from generation to generation, indeed, that the Divine Voice heard at Sinai still reverberates in the world, so that those “tuned-in” to it can still hear it. According to this, Yigal Amir can claim that he was acting according to Divine will. Is that all it takes? That and the opportunity to act? It is depressing to think so, and if this is too simplistic, still it has validity (think Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and the start of World War One). It is depressing because it leads us to a conclusion that no matter how orderly we can make our society, we will always be at the mercy of such actors.

And as my reading material seemed to fall into place in a significant manner, another item plopped onto my table. When I started this article the farthest thing from my mind was Yigal Amir. Yet here he is. And on the evening news after I wrote the previous paragraphs, a right-wing Israeli pundit appeared on the Israeli equivalent of Fox News and called for Amir’s release from prison. Out of the blue. Things come together in unexpected ways.

This is what the protesters against the judicial reform mean when they claim that the ruling coalition is controlled by Messianics. From their point of view the ruling coalition is based on cooperation with an unknowable entity—one that does not base its world view on standard, rational politics, rather it is a faith-based entity. An entity out of which can appear a Yigal Amir. From their point of view it is impossible to do business as usual with such Jews, though they have proven time and again to be among the most fervent Zionists in the room. How have they done so? By having many more children than is considered prudent in a modern upwardly mobile society, by educating those children in Jewish tradition with a hope that they will be observant Jews as adults, and by encouraging their children to strive for excellence in their obligatory military duty, and to find a profession that will allow them to contribute to the advancement of Israeli society, in a way through which they are giving more than they receive.

These last points were once the calling card of secular Zionists. That is part of their difficulty. They see themselves as being superseded and resent it. The religious-Zionists on their part say “We learned Zionism from you! You are welcome back to the party!” Here we come to the pivot point of the weighing scale. Whereas the traditional religious-Zionist political approach was moderate, seeing themselves serving as a bridge between modernity and tradition, the advent of the Intifadas and the Rabin government’s deal with the devil Arafat—and the thousands of murdered Jews in the wake of that deal—led to a strengthening of the hard ideological right. It is important to note that the entire political spectrum moved to the right at that time, so quickly and so decisively that in the elections after Rabin’s murder, the right won, overcoming the swell of sympathy for Rabin from across the political spectrum. In the present, after some time has passed, many of the national-Religious are asking what happened to the good old days, when they worked together with their secular brothers. In addition, the hard-right ideologues in the governing coalition, though working to advance their interests, have remarkably toned down their rhetoric, as happens when firebrands—enthusiasts—finally achieve some measure of sanctioned influence, like being a minister in a government.

I am leaving much out in this account, but one general statement can be made about the Israeli people. They are in the midst of a self-reckoning to determine their identity. All are involved: secular, ultra-orthodox, religious Zionists…even Israeli Muslim Arabs and Bedouin. For whatever reasons, nefarious or not, the eyes of the world are upon the Holy Land, relentlessly, as if the outcome of this self-reckoning has some bearing on all.

Interesting, but might take exception to your statement that Sabbatai Zevi "managed to convince the entire Jewish diaspora of the mid seventeenth century that he was the Messiah." He had a lot of followers, and there was certainly a contagion. This article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sabbateans, for instance, includes a list of Sabbatai's opponents. So, that's my quibble. -- Bob (graboyes.substack.com)

It's interesting, isn't it, how things have a habit of coming together in different ways, like the universe is trying to tell you something. But a question I'd like to ask, and which I asked in a study group a couple of months back (without a definitive answer)is: how come so many presumably intelligent people could believe someone was the Messiah just because they, or an advocate of theirs, says so? I mean, if someone said to me "I'm the Messiah" I'd probably respond by saying "Yes, and I'm the sugar plum fairy". Surely people can expect some form of proof?