Leopold Bloom, Jew or Not

"Is he a jew or a gentile or a holy Roman or a swaddler or what the hell is he?"

A google search on “Is Leopold Bloom Jewish?” returns a substantial number of links to essays discussing this question. All of them fall into three categories: Bloom is a Jew, Bloom is not a Jew, or Bloom is somewhat of a Jew. Since Bloom is the main character of the greatest work of fiction in the English language, this determination is an important subject for criticism. On the most primitive level, and a one we encounter in Ulysses, the definition of a Jew determines who will be the object of antisemitic persecution. Joyce, who orchestrated this confusion about the Jewishness of Bloom, addresses antisemitism in Ulysses in a way that highlights the evil that is at its core and contrasts it with human decency. This is the first in a series of articles dealing with Jewish aspects of Ulysses. All quotes of Ulysses are from “The Joyce Project” and link to that fabulous site. In Chrome, the links will take you to the precise quote. In Edge it works about half the time. If the links are not working, on a computer right-click the link and choose “open in a new window.” On a smartphone, press and hold on the link until the sub-menu appears and choose “open in browser.” I have found that after doing this one or two times, just pressing on the link as it appears in the article will jump to the quote.

Bloom

James Joyce did not hide his interest in Jews while writing Ulysses. Ettore Schmitz once said to Joyce's brother Stanislaus: "Tell me some secrets about Irishmen. You know your brother has been asking me so many questions about Jews that I want to get even with him."1 Joyce remarked on the similarity between the Jews and the Irish. "They were alike, he declared, in being impulsive, given to fantasy, addicted to associative thinking, wanting in rational discipline" (JJ 395). He insisted to Wyndham Lewis that the destinies of the Irish and the Jews were alike (JJ 515). There were two traits thought by Joyce to be characteristic of Jews that particularly interested him, "their chosen isolation, and the close family ties which were perhaps the result of it" (JJ 373). It is understandable then, that when Joyce sent his Odyssey-based schemata to Carlo Linati—a move that led (along with his similar presentation of a skeleton key to Stuart Gilbert) to a generation of criticism that was based upon the exploration of modern Irish parallels with the Greek classic—he could at the same time claim that Ulysses was "an epic of two races (Israel-Ireland)" (JJ 521 n.).

According to traditional Jewish law, a Jew is one born of a Jewish mother or one who converts to Judaism. Joyce, who asked endless questions about Jews, was aware of this. Evidently Bloom's mother, Ellen Higgins Bloom, was not Jewish, though it is difficult to ascertain. Her maiden name doesn't seem Jewish, and her "appearance" in Ulysses is accompanied by a Catholic vocabulary.2 Bloom's father converted to Christianity the year he was married, an act that would seem odd had Ellen Higgins been Jewish.3 But Bloom's parental lineage shouldn't matter, at least to the Christian world, because he himself submits to the eternal Christian demand of the Jew. He accepts Christianity, more than once: three times by his own account.

Had Bloom and Stephen been baptised, and where and by whom, cleric or layman?

Bloom (three times), by the reverend Mr Gilmer Johnston M. A., alone, in the protestant church of Saint Nicholas Without, Coombe, by James O’Connor, Philip Gilligan and James Fitzpatrick, together, under a pump in the village of Swords, and by the reverend Charles Malone C. C., in the church of the Three Patrons, Rathgar. Stephen (once) by the reverend Charles Malone C. C., alone, in the church of the Three Patrons, Rathgar.

Joyce went to great lengths to negate Bloom's "Jewishness." Critics (including Jewish critics) have consistently labeled him a Jew, even while acknowledging his Christian credentials. Why is that? It is true that Bloom himself displays some ambivalence towards the matter. "Your God was a jew. Christ was a jew like me." Bloom regrets having "treated with disrespect certain beliefs and practices," Jewish in nature, but we are not led to believe through his actions of the day that this is because he felt obligated to respect them. Bloom, relating to Stephen the story of his antisemitic encounter earlier in the day, tells him that he is not Jewish ("though in reality I'm not"). Later, Bloom doesn't think that Stephen got the point, but Stephen was aware of Bloom's status: "He thought that he thought that he was a jew whereas he knew that he knew that he knew that he was not." Joyce refines this obscurity into a single definitive question, which serves as a prelude to the main display of anti-Semitism in Ulysses--Bloom's confrontation with the Citizen: "Is he a jew or a gentile or a holy Roman or a swaddler or what the hell is he?" Though the citizen may repulse us, he asks the pertinent question.

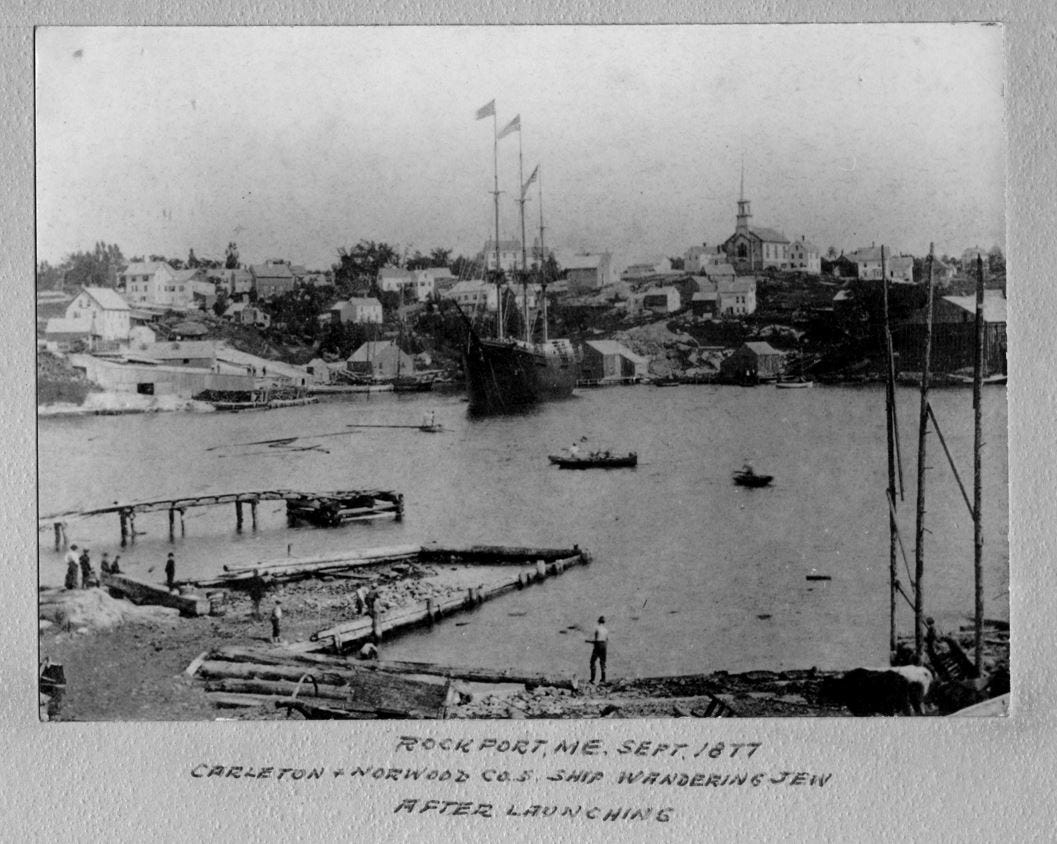

What was Joyce doing here? We return to what Joyce considered to be the Jews’ “chosen isolation.” Bloom is a sympathetic character. Alert, clever, curious, sensual, and full of internal contradictions, there is enough in Bloom to draw us towards him, to see something of ourselves in him: an imperfect human being making his way through life during a normal day. However, Bloom does not choose isolation in the book, rather he seeks out and enjoys human intercourse. Joyce created in Bloom an “uber-jew”, a character type that, though not Jewish, is encumbered with the weight of an overlayed Jewish identity. This identity is sometimes assumed voluntarily by Bloom and sometimes it is imposed upon him, as it is sometimes welcomed by him and sometimes not. Bloom’s isolation, though, is entirely imposed from without. To isolate Bloom Joyce “semitized” him. The forced isolation of the Jew, the Jew’s ostracization by society, has as its mythic foundation the fable of the Wandering Jew. As insistent as critics have been in labeling Bloom a Jew, they have been no less insistent on affixing to him the motif of the Wandering Jew, not without prompting by Joyce. It is an inviting avenue for literary exegesis. Bloom wanders throughout Dublin, a wandering Jewish Ulysses, the incarnation of the Joycean Greek-Jew-Irish trinity. But the Wandering Jew motif is Jewish in the same sense that anti-Semitism is Jewish, and Joyce knew that, and so subsumes it into a consideration of the human condition at large:

Every life is many days, day after day. We walk through ourselves, meeting robbers, ghosts, giants, old men, young men, wives, widows, brothers-in-love, but always meeting ourselves.

The treatment of Bloom as the Wandering Jew cannot give an accurate account of Joyce's intentions but can only increase the obscurity of them. Bloom’s isolation must serve a different purpose. And whatever this purpose is, another question presents itself: could Joyce have achieved it without disguising Bloom as a Jew?

He presents Bloom as the twentieth century anti-hero or Everyman, just a normal person going about his daily business, while at the same time he superimposes upon Bloom attributes of the great heroes of the West (Moses, Ulysses, Jesus). This dialectic suggests Bloom’s appearance in Ulysses is high comedy. A comic Bloom seen as representing Judaism is degrading to the Jewish people; the measure of a Jew is not by how non-Jewish he appears and acts. Yes, Bloom plays both sides now and then, but he hardly acts in a manner that should lead a reader who is acquainted with Jews--and who respects them--to believe that he has in Bloom a fair portrayal of a Jew. Is Bloom's being a cuckold definitive of the Jew? Or his being a “womanly man?” Or if the boys at the pub have it right, does Bloom have "sort of a queer odour," or a "bottlenose," and are these definitive of the Jew? This “degradation” was pointed out to Joyce by a young Harvard student, to whom Joyce replied that he had "written with the greatest sympathy about the Jews" (JJ 709). If Bloom were indeed a Jew, the student would have had a case against Ulysses. Joyce, in disguising Bloom as a Jew, put the lie to anti-Semitism, to the anti-Semitism of the characters in the book and to the prejudices of the book's readers and critics. To put it differently: considering Bloom's voluntary baptism three times over, why do we, lay readers of Ulysses and professional critics alike, let alone the characters in the book, deny the validity of his Christianity? At the very least we should free him of his Judaism.

In the chapter of Ulysses that introduces him, Bloom reads a prospectus dealing with the reclamation of tracts of the Holy Land. He imagines a modest “redemption” in Palestine, where there are “Crates lined up on the quayside at Jaffa, chap ticking them off in a book, navies handling them in soiled dungarees.” He rejects the vision as unrealistic (as did most Jews at the time) but shares a moment of eye contact with the Zionist pork butcher, the first hint of a Jewish nexus. Later, Bloom contemplates “reclaiming” a part of his own back yard, a private return to a personal Zion: “Reclaim the whole place. Grow peas in that corner there.” In the later dream-like sections of the book, Bloom’s breakfast ritual is called “Burnt Offering,” and the outhouse “holy of holies.” Poor Bloom. He wants to eat breakfast and relieve himself and Joyce has him become a priest making offerings and visiting the holy of holies.

There is a messianic figure in the book of Zecharia, ish Żemaĥ, (the “shoot,” according to Soncino; or “The Branch,” New English Bible), who according to the prophesy “Behold a man whose name is Żemaĥ, and who shall grow up out of his place; and he shall build the temple of the Lord:” (Zech 6:12). As the name of one who shall build the Temple, Żemaĥ carries messianic implications. Three major traditional commentaries--Rashi, Ibn Ezra and Radak agree that in this passage Zechariah is referring to Zerubbabel.4 The Temple was in fact rebuilt in Zerubbabel's day, although at an agonizingly slow pace and on a smaller scale than the first Temple, and, regardless of the eventual failure to reinstate the kingship of the Davidic line, a significant messianic hope was fostered that had a slowly developing counterpart in the events of the period. Rashi and Radak explain the verb yitsmah as referring to the character of Zerubbabel's reconstruction--"little by little" (meyat meyat), as a plant grows. These commentators were interpreting a delicate subject in the light of certain decisive historical realities, with one end in mind of protecting a people from its own traditionally explosive prophetic reaches.

The Hebrew tahat means "under," or "beneath," and umi-tahtav means "and from under him." In the phrase umi-tahtav yitsmah (Zech 6:12), the combined literal meaning is senseless: "and he will grow (plant-like) from beneath himself," but context and tradition combine to clarify the situation. There are two related approaches to this passage. The approach of the three previously mentioned commentators is to say that this phrase means: "and he shall rise up out of his place," and this the approach adopted in the English translations. The other approach, that Rashi acknowledges but dismisses, holds also that the name Żemaĥ refers to Zerrubabel, but that umi-tahtav yitsmah means: "and from his seed (from 'beneath' him, from his progeny) the King Messiah (Melekh Ha-mashiah) "shall come forth."

In Ulysses, the messianic overtones connected with ish Żemaĥ are retained in the name’s anglicization to “bloom,” and in the character Bloom. Bloom is not the Jewish Messiah, is not “Messiah ben Joseph or ben David.”5 He is a different kind of messiah, or "anointed one." In Jewish tradition the main act of the Messiah is to rebuild the Temple. The messiah Bloom envisions a new Jerusalem, or Bloomusalem, and a new Ireland:

BLOOM

My beloved subjects, a new era is about to dawn. I, Bloom, tell you verily it is even now at hand. Yea, on the word of a Bloom, ye shall ere long enter into the golden city which is to be, the new Bloomusalem in the Nova Hibernia of the future.

(Thirty two workmen, wearing rosettes, from all the counties of Ireland, 457under the guidance of Derwan the builder, construct the new Bloomusalem. It is a colossal edifice with crystal roof, built in the shape of a huge pork kidney, containing forty thousand rooms. In the course of its extension several buildings and monuments are demolished. Government offices are temporarily transferred to railway sheds.484 Numerous houses are razed to the ground. The inhabitants are lodged in barrels and boxes, all marked in red with the letters: L. B. Several paupers fall from a ladder. A part of the walls of Dublin, crowded with loyal sightseers, collapses.)

In having this shadow-world culmination of Jewish prophecy occur in a brothel, Joyce is hammering home a major theme of Ulysses. It is the interchangeability of the sacred and the profane, and that in itself is profane. Or is not. We will explore this further in the next installment, while at the same time strengthening the association that I have proposed between Bloom and ish Żemaĥ. We will leave our larger questions unanswered until the final installment of this series.

As a passing note, whatever his reasons for the “uber-Jew” Bloom, the ironies of this treatment must have been clear to Joyce near the end of his life before the Second World War. Joyce himself helped about twenty people escape the Nazis (JJ 709). Laughingly, he was refused entry to Switzerland by the Swiss authorities, who thought he was a Jew! (JJ 736). Obviously, they had confused him with his most famous creation (Bloom, incidentally, was Jew enough for the Nazis). It took a legion of prominent Swiss to testify as to Joyce's being a kosher gentile before the authorities begrudgingly relented and allowed him to enter (JJ 736-37). Bloom, a humane and sensitive comic figure, undeniably relieves the twentieth century tragedy of the human condition, which is its dehumanization towards a mechanical, senseless anonymity, in a world without compassion. However, as Joyce must have known in the end, the Jewish condition in Europe was tragic beyond all relief.

Richard Ellman, James Joyce (New York: Oxford University Press, 1959; revised 1982; corr. paper 1983) p. 374. All further references in text as "(JJ pg.)."

There was a Jewish Higgins in Dublin (JJ 513). Ellen's father may have been Jewish but her mother's maiden name of Hegarty indicates that she was not.

Rudolph's conversion was not out of religious conviction. Otherwise, his passing on to Bloom a Jewish consciousness--watered-down as it may have been-would have been inexplicable. He even read to Bloom passages from the Passover Haggadah in Hebrew ("…reading backwards with his finger to me.").

Rabbi Shlomo Yitshaki (Rashi), 1040-1104. His is the principal commentary on the Torah and Talmud; Abraham Ibn Ezra, 1092-1167; Rabbi David ben Yosef Kimhi (Radak), 1160-1235. Radak’s commentary on the Prophets and Writings influenced Christian translations of the Bible.

There is a tradition holding that the coming of Messiah ben David will be preceded by the coming of Messiah ben Joseph, who will lead Israel during the initial apocalyptic wars.

I broke my golden rule, which is to not read anything much about a book before I've read it, as I prefer to come to a text tabla rasa. But I found this really interesting, and as luck would have it, the reservation I placed on Ulysses at my library has come to fruition, so to speak: I picked up the book yesterday. Corey Smith (https://coreyswords.substack.com/) assures me I will love it, though I have to confess I am daunted by it. Wish me luck!

Off the subject of Ulysses, it really pisses me off that jews are being persecuted again today. I think the underlying cause is simple envy. Jews tend to be smart, an they're successful. Exactly what those who want to centralize everything don't want people to be.